The city walls of Ayutthaya

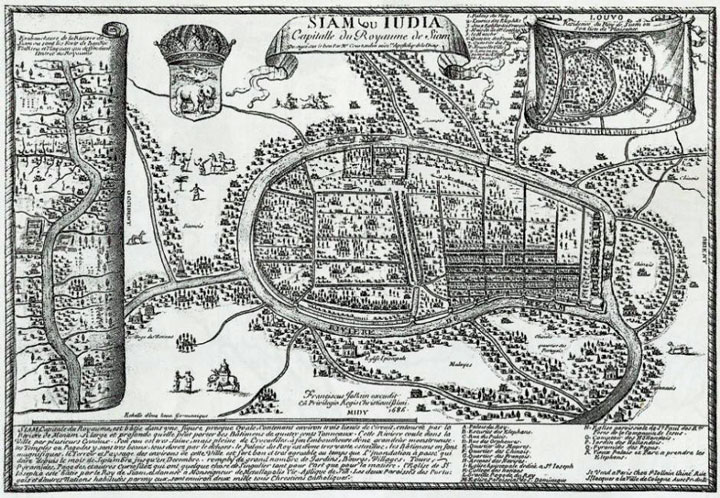

Map of Ayutthaya 1686

Last year in November I wrote two contributions for this blog about the historic city walls of Chiang Mai and Sukhothai. Today I would like to reflect on the - largely disappeared - city wall of Ayutthaya, the old Siamese capital.

Ayutthaya, which in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was described by many astonished Western visitors as a picturesque, almost enchanting metropolis, was without doubt one of the most beautiful and breathtaking cities in Asia and perhaps even in the world. Even Dutch merchants such as Jeremias van Vliet, who was chief merchant of the VOC in Ayutthaya from 1639 to 1641, who are known for their sobriety, lacked superlatives to describe this colorful and wonderful city. The imaginative palaces and magnificent temples along a network of busy canals evoked reminiscences of Venice, Bruges and Amsterdam among Western travelers. The first view they got of the city was on approach to the city, by ship, across the Chao Phraya. And that first image was determined by the high, imposing whitewashed city walls, above which the orange-red and deep green glazed roofs and the gold-colored chedis stood out against the sweltering, azure sky.

Ayutthaya emerged circa 1350 along the eastern bank of the Chao Phraya as a satellite city of Sukhothai. By making clever use of the three rivers that flowed in the immediate vicinity (the Lopburi River, Pa Sak River and the Men Nam or Chao Phraya) and digging a network of navigable canals and defensive moats, the in the fifteenth century rapidly expanding city into what can hardly be described otherwise as a very large and very strategically located island. This location was certainly not accidental: Ayutthaya was just outside the tidal limit of the Gulf of Siam, which made direct attacks from the sea more difficult while minimizing the risk of flooding. The location within a belt of canals and rivers and in the vicinity of swamps and moist soils that were not easy to traverse, where the malaria mosquitoes ruled, made Ayutthaya a very difficult city to take.

Until the end of the sixteenth century, only a few palace grounds in the city were walled with sandstone. The rest of the city was protected by thick earthen ramparts topped by wooden palisades built under the reign of Ramathibodi I (1350-1369). Hardly anything has survived of these original defenses, but fragments of this first rampart can still be found on the grounds of Wat Ratcha Pradit Sathan. These constructions were not resistant to the Burmese and on August 30, 1569 the city was taken. It was the Burmese king Maha Thammaracha, who reigned from 1569 to 1590, who improved the city's defensive infrastructure in response to a threatened Cambodian invasion. He ordered the breaking down of the earthen ramparts and the erection of the brick city walls. The fact that gunpowder and cannons were increasingly used to destroy defensive positions may also have contributed to this drastic decision.

Despite the fact that this was a huge job, this ambitious project was completed in just a few years. The project was completed in 1580 by extending the city walls to the rivers. 12 massive city gates and 12 water gates were built in the ramparts that gave access to the capital. Each of these gates was wide enough for an ox-cart to pass through, and was crowned by a metre-high spike painted blood red. The choice of this number was in all probability not a coincidence but symbolically related to the 12-year cycle of the Chinese zodiac. Not for nothing was the name of the city in Sanskrit Maha Nagara Dvaravati what freely translated 'Great City with Gates' means. In addition to these large gates, however, there were also several dozen smaller gates and passages crowned with graceful arches, often just wide enough for an adult to pass through or which were part of the complex irrigation system. A beautiful example of such a gate, but in urgent need of restoration, is the Pratu Chong Kut, which can be found behind the Wat Rattanachai City Council School.

The city walls themselves presented a majestic sight. To say they were monumental is an understatement. They were on average about 2,5 meters thick and 5 to 6,5 meters high and equipped with embrasures and sturdy battlements. They were erected on a solid foundation consisting of a foundation of compactly packed earth, laterite and crushed stone that had been buried several meters deep. On the inside of the walls, there was an earthen embankment 3 to 4 meters high and 5 meters wide along the entire length, which was used for the patrols of the city guards. Where the ramparts did not border the rivers, they were secured by a moat twenty meters wide and at least six meters deep. The longest side of the wall was more than 4 kilometers long, the shortest 2 kilometers. A partial reconstruction of a city wall can be found at Hua Ro Market, while a large part of the base can still be found at the northern wall of the Grand Palace.

In 1634, just over half a century after the Burmese completed the brick city walls, the Siamese king Prasat Thong (1630-1655) had the city walls renovated and considerably strengthened. Between 1663 and 1677, at the request of King Narai (1656-1688), all city walls were taken over by the Sicilian Jesuit and architect Tommaso Valguernera, who had built the San Paulo church in the Portuguese enclave a few years earlier. When in 1760 the threat of a Burmese invasion once again became very real, the former King Uthumphon, who had reigned in 1758, returned from the monastery to which he had retreated to organize the defense of the city. He mobilized a large part of the population and in no time managed to erect a second, formidable city wall in front of the Great Palace, while the waterways and canals were closed off with huge teak trunks. A very small part of this improvised but very solid defense structure has been preserved along the U-Thong Road between Wat Thammikarat and Klong Tho.

The VOC chief merchant Jeremias Van Vliet wrote in 1639 that Ayutthaya had no significant stone bastions or forts. Other accounts of the period confirm this story. There was only talk of defensive positions protected by palisades. Apparently, the inhabitants of the Siamese capital felt so safe behind the city walls that they had no need for additional forts. On the fairly reliable city map that the Frenchman Nicola Bellin in 1725 L'Histoire Générale des Voyages published by Abbé Antoine Prévost, however, no fewer than 13 brick fortifications can be found, almost all of which are part of the city walls. In concrete terms, this means that in less than a century the city walls were considerably expanded and strengthened. This, of course, had everything to do with the almost permanent threat of war emanating from neighboring Burma. The main forts were Sat Kop Fort, Maha Chai Fort and Phet Fort which controlled the main entrances to the city by water. Historians assume that the Siamese were helped in drawing the plans for these forts by Portuguese military engineers who also supplied or had many of the required guns cast in local workshops. However, about 1686, it was the French officer de la Mare, who had been part of the first French diplomatic mission to the court of King Narai, who was charged with building and renovating a number of forts. De la Mare was not an engineer but a river pilot, but this apparently did not prevent the French from working on the further renovation of the military fortifications until 1688.

At least 11 of these forts more or less survived the looting and destruction of 1767. They might have been too massive and sturdily built to be destroyed one, two, three by the Burmese troops. From a French map published in Paris in 1912 by the Commission archéologique de l'Indochine shows that at the beginning of the twentieth century 7 of these forts still remained. Only two of these forts survive today: the largely dilapidated Pratu Klao Pluk Fort at Wat Ratcha Pradit Sathan and the restored Diamant Fort opposite Bang Kaja that protected the southern entrance to the city along the Chao Phraya. However, both provide a good insight into military architecture from the last half of the seventeenth century.

Diamond Fort Ayutthaya

After the fall and destruction of Ayutthaya in 1767, the city walls quickly fell into disrepair. It was under the reign of Rama I, (1782-1809) the founder of the Chakri dynasty, that the fate of the largely useless but once impressive city walls was finally sealed. He had a large piece demolished and used the recovered materials in the construction of his new capital Bangkok. The stones from Ayutthaya also ended up in the dam that was built in 1784 in the Lat Pho channel in Phra Pradaeng to prevent the progressive salinization further inland. Rama III (1824-1851) gave the final blow by demolishing the rest of the city walls. Much of the latter material was used for the construction of the giant chedi at Wat Saket. When it collapsed, the rubble formed the core of what later became the GoldenMount or would become Golden Hill. The last remnants of the walls disappeared in Ayutthaya in the year 1895 when Governor Phraya Chai Wichit Sitthi Satra Maha Pathesatibodi built the U-Thong Road, the ring road around the city. With this, one of the last tangible witnesses of the greatness that Ayutthaya once possessed disappeared…

Another interesting piece of history Lung Jan.

I would like to add a small addition, because I did not read when Ayutthaya came back into Siamese hands between 1569 and 1634.

After the Burmese conquered the city in 1569, they appointed the defecting Siamese governor Dhammaraja (1569-90) as vassal king. His son, King Naresuan (1590-1605) thought that the kingdom of Ayutthaya could stand on its own two feet again and by 1600 he had driven out the Burmese.

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Ayutthaya_Kingdom#Thai_kingship