The Dutch war cemeteries in Kanchanaburi

A visit to Kanchanaburi War cemetery is a captivating experience. In the bright, sweltering light of the Copper Thug blazing mercilessly overhead, it seems that row after row of the clean-lined uniform tombstones in the lawns trimmed to the nearest millimetre, reaching to the horizon. Despite the traffic in the adjacent streets, it can sometimes be very quiet. And that's great because this is a place where memory slowly but surely turns into history...

This beautifully landscaped Garden of Death is a place that, despite the heat, encourages reflection. After all, military graveyards are not only 'Lieux de Memoire' but also and above all, as Albert Schweitzer once so beautifully put it, 'the best advocates for peace...

Of the 17.990 Dutch prisoners of war who were deployed by the Japanese army between June 1942 and November 1943 in the construction and subsequent maintenance of Thai-Burma Railway nearly 3.000 succumbed to the hardships incurred. 2.210 Dutch victims were given a final resting place at two military cemeteries in Thailand near Kanchanaburi: Chungkai War Cemetery en Kanchanaburi War Cemetery. After the war, 621 Dutch victims were buried on the Burmese side of the railway Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery.

Chungkai War Cemetery – Yongkiet Jitwattanatam / Shutterstock.com

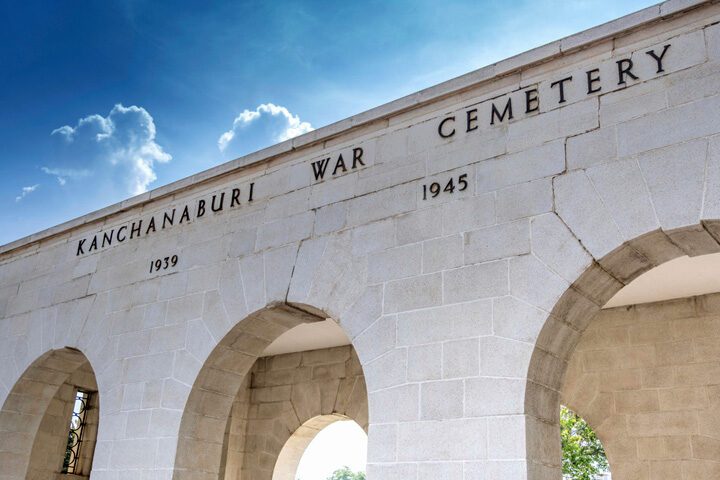

Op Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, (GPS 14.03195 – 99.52582) which is about halfway between the place of the same name and the infamous bridge over the Kwai, 6.982 war victims are commemorated. Among them, the British, with 3.585 killed in action, form the largest group. But also Dutch people and Australians with 1.896 and 1.362 military deaths respectively are well represented on this site. On a separate Memorial are the names of 11 men of the Indian Army who were given a final resting place in nearby Muslim cemeteries. It Indian Army was in the 18e century from the private army of the British East India Company, the counterpart of the Dutch VOC, and has been making since the 19e century an integral part of the British armed forces. The grave markers, horizontal cast iron nameplates on granite bases, are uniform and of the same size. This uniformity refers to the idea that all the fallen made the same sacrifice, regardless of rank or rank. In death everyone is equal. Originally there were white wooden grave crosses here, but they were replaced by the current tombstones at the end of the fifties and early sixties.

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery

Two collective graves contain the ashes of 300 men who were cremated during the outbreak of the cholera epidemic in May-June 1943 in Nieke Camp. Their names are mentioned on the panels in the pavilion on this site. The site's post-war redevelopment and austere design – a stylized expression of understated grief – was envisioned by CWGC architect Colin St. Clair Oakes, a Welsh war veteran who, in December 1945, along with Colonel Harry Naismith Hobbard, was part of a committee that made an inventory of the war graves in countries including India, Burma, Thailand, Ceylon and Malaysia and decided where collective cemeteries would be built.

Kanchanaburi War Cemetery was started by the British at the end of 1945 as a collective cemetery. The site is not far from the site of Kanburi Camp, one of Japan's largest base camps, where almost every Allied prisoner of war deployed to the railway first passed through. The vast majority of the Dutch who were interred on this spot had served in the army, 1.734 to be exact. Most of them came from the ranks of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNIL). 161 Among them had served in one capacity or another with the Royal Navy and 1 who died belonged to the Dutch air force.

The highest-ranking Dutch soldier who was interred here was Lieutenant Colonel Arie Gottschal. He was born on July 30, 1897 in Nieuwenhoorn. This KNIL infantry officer died on 5 March 1944 in Tamarkan. He is buried in VII C 51. Another interesting grave is that of Count Wilhelm Ferdinand von Ranzow. This nobleman was born on April 17, 1913 in Pamekasan. His grandfather, Imperial Count Ferdinand Heinrich von Ranzow had North German roots and had worked as a senior civil servant in the Dutch East Indies where he was resident of Djokjakarta between 1868 and 1873. In 1872 the family was incorporated into the Dutch nobility at KB with hereditary title. Wilhelm Ferdinand was a professional volunteer in the KNIL and served as a brigadier/mechanic in the 3e battalion of engineers. He died on September 7, 1944 in Camp Nompladuk I.

The highest-ranking Dutch soldier who was interred here was Lieutenant Colonel Arie Gottschal. He was born on July 30, 1897 in Nieuwenhoorn. This KNIL infantry officer died on 5 March 1944 in Tamarkan. He is buried in VII C 51. Another interesting grave is that of Count Wilhelm Ferdinand von Ranzow. This nobleman was born on April 17, 1913 in Pamekasan. His grandfather, Imperial Count Ferdinand Heinrich von Ranzow had North German roots and had worked as a senior civil servant in the Dutch East Indies where he was resident of Djokjakarta between 1868 and 1873. In 1872 the family was incorporated into the Dutch nobility at KB with hereditary title. Wilhelm Ferdinand was a professional volunteer in the KNIL and served as a brigadier/mechanic in the 3e battalion of engineers. He died on September 7, 1944 in Camp Nompladuk I.

Among those who were given a final resting place here and there, we find relatives of each other here and there. The 24-year-old Johan Frederik Kops from Klaten was an artilleryman in the KNIL when he died on 4 November 1943 in Kamp Tamarkan II. He was buried in grave VII A 57. His father, the 55-year-old Casper Adolf Kops, was a sergeant in the KNIL. He succumbed in Kinsayok on February 8, 1943. The Dutch death toll in Kinsayok was very high: at least 175 Dutch POWs died there . Casper Kops was buried in grave VII M 66. Several brother pairs are also buried on this site. Here are some of them: The 35-year-old Jan Kloek from Apeldoorn, just like his two years younger brother Teunis, was an infantryman in the KNIL Jan died on 28 June 1943 in the improvised field hospital in Kinsayok, probably as a victim of the cholera epidemic that wreaked havoc in the camps along the railway line. He was given a final resting place in the collective grave VB 73-74. Teunis would succumb a few months later, on October 1, 1943 in Takanon. He was buried in VII H 2.

Gerrit Willem Kessing and his three years younger brother Frans Adolf were born in Surabaya. They served as soldiers in the KNIL infantry. Gerrit Willem (collective grave VC 6-7) died on July 10, 1943 in Kinsayok, Frans Adolf succumbed on September 29, 1943 in Kamp Takanon (grave VII K 9). George Charles Stadelman was born on August 11, 1913 in Yogyakarta. He was a sergeant in the KNIL and died on June 27, 1943 in Kuima. He was buried in grave VA 69. His brother Jacques Pierre Stadelman was born on July 12, 1916 in Djokjakarta. This watchman in the KNIL artillery died on December 17, 1944 in Tamarkan. At least 42 Dutch prisoners of war died in this last camp. Jacques Stadelman is buried in grave VII C 54. The brothers Stephanos and Walter Artem Tatewossianz were born in Baku in Azerbaijan, which was then still part of the Russian tsarist empire. The 33-year-old Stephanos (VC 45) died on April 12, 1943 in Rintin. At least 44 Dutch people died in this camp. His 29-year-old brother Walter Aertem (III A 62) died on August 13, 1943 in Kuie. 124 Dutch people would lose their lives in this last camp…

In the much less visited Chungkai War Cemetery (GPS 14.00583 – 99.51513) 1.693 fallen soldiers are buried. 1.373 British, 314 Dutch and 6 men of the Indian Army. The cemetery is not far from where the River Kwai divides into the Mae Khlong and the Kwai Noi. This cemetery was established in 1942 next to the Chungkai prisoner of war camp, which served as one of the base camps during the construction of the railway. A rudimentary inter-allied field hospital was set up in this camp and most of the prisoners who succumbed here were interred on this site. Just like in Kanchanaburi War Cemetery CWGC architect Colin St. Clair Oakes was also responsible for the design of this cemetery.

Of the Dutch who were given a final resting place here, 278 belonged to the army (mainly KNIL), 30 to the navy and 2 to the air force. The youngest Dutch soldier to be buried here was 17-year-old Theodorus Moria. He was born on August 10, 1927 in Bandung and died on March 12, 1945 in the hospital of Chungkai. This Marine 3e class was buried in grave III A 2. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the sergeants Anton Christiaan Vrieze and Willem Frederik Laeijendecker in graves IX A 8 and XI G 1, at the age of 55, were the oldest fallen soldiers at Chungkai War Cemetery.

The two highest-ranking Dutch soldiers at the time of their death were two captains. Henri Willem Savalle was born on February 29, 1896 in Voorburg. This career officer was an artillery captain in the KNIL when he died of cholera on 9 June 1943 in the camp hospital in Chungkai. He is buried in VII E 10. Wilhelm Heinrich Hetzel was born on October 22, 1894 in The Hague. In civilian life he was a doctor of mining engineering and an engineer. Just before they left for the Dutch East Indies, he married Johanna Helena van Heusden on 19 October 1923 in Middelburg. This reserve captain in the KNIL artillery succumbed to Beri-Beri on August 2, 1943 in the camp hospital of Chungkai. He is now buried in grave VM 8.

The two highest-ranking Dutch soldiers at the time of their death were two captains. Henri Willem Savalle was born on February 29, 1896 in Voorburg. This career officer was an artillery captain in the KNIL when he died of cholera on 9 June 1943 in the camp hospital in Chungkai. He is buried in VII E 10. Wilhelm Heinrich Hetzel was born on October 22, 1894 in The Hague. In civilian life he was a doctor of mining engineering and an engineer. Just before they left for the Dutch East Indies, he married Johanna Helena van Heusden on 19 October 1923 in Middelburg. This reserve captain in the KNIL artillery succumbed to Beri-Beri on August 2, 1943 in the camp hospital of Chungkai. He is now buried in grave VM 8.

At least three non-military personnel are buried on this site. The Dutch citizen JW Drinhuijzen died at the age of 71 on 10 May 1945 in Nakompathon. His compatriot Agnes Mathilde Mende died on April 4, 1946 in Nakompathon. Agnes Mende was employed as 2e commies of the NIS and was born on April 5, 1921 in Djokjakarta. Matthijs Willem Karel Schaap had also seen the light of day in the Dutch East Indies. He was born on April 4, 1879 in Bodjonegoro and died 71 years later, on April 19, 1946 to be precise in Nakompathon. They were buried next to each other in the graves in plot X, row E, graves 7, 8 and 9.

Both sites are managed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), the successor to the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) which was established during the First World War to give a dignified final resting place to the fallen of the British Commonwealth. The maintenance of the Dutch graves on their fields of honor is also taken care of by this organization in consultation with the Dutch War Graves Foundation. There are also 13 other Dutch military and civilian cemeteries in Asia. Mainly in Indonesia, but also in, for example, Hong Kong, Singapore and the South Korean Tanggok.

Extensively and carefully described, that must have been quite a study. Beautiful photos added.

Now history, but then raw reality. May the fallen men and single woman rest in peace.

And question about the stone of Count Von Ranzow, it says Brig. Gl. Doesn't this stand for Brigadier General? This seems more consistent with his noble title rather than sergeant/mechanic.

Dear Piotrpatong,

I have also wondered this myself, but a brigadier general of barely 31, noble title or not, is very young… I am not a connoisseur of the Dutch ranks during WWII or in the KNIL, but I think the rank of Brigadier General introduced after World War II (British connection Princess Irenebrigade…) and is no longer used… Just to be sure, I took his file card from the War Graves Foundation and there his rank is listed as follows: Brigadier Gi and not Gl… (Possibly Gi is an abbreviation for genius…) On his original index card as a Japanese prisoner of war which is kept in the Ministry of the Interior – Stichting Administratie Indische Pensioenen is listed as a rank brigadier mechanic in the 3rd Battalion Engineer Corps of the KNIL….At the head a KNIL battalion had at best a colonel, but certainly not a brigadier general…

Let's also not forget that there was a Japanese order to KILL ALL PRISONERS. Fortunately, 2 atomic bombs dropped on Japan hastened that surrender, although on August 9 the Japanese made no attempt to do so. Presumably the Soviet storm over Manchuria on Aug. 10, which incidentally continued until the signing of the capitulation Oct. 2. to bring the whole area under their control for a while, the final tipping point to capitulation.

see with Google: “Japanese order to kill all prisoners Sept 1945”

I know, this article is about the Dutch cemeteries.

There is much and much less interest in the 200.000 to 300.000 Asian workers on the railway, of whom a much larger percentage lost their lives. Many people from Malaysia, Burma, Ceylon and Java. They are hardly remembered. This is stated in this article in the New York Times:

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/10/world/asia/10iht-thai.1.10867656.html

Quote:

Worawut Suwannarit, a history professor at Kanchanaburi Rajabhat University who has spent decades trying to get more recognition for the Asian laborers, has come to a harsh and bitter conclusion.

“This is why these are called undeveloped countries – Third World countries,” he said. “They don't care about their people.”

Others blame the British, the colonial rulers before and after the war in both Burma and Malaya, the two countries that sent the most workers to the railway, for not doing more to honor the dead.

The Thai government has had little incentive to honor the dead because few Thais worked on the railway.

No.. the Thai government does not want to be reminded of the Thai attitude towards the Japanese. Many people living in Thailand – especially Chinese – were forced to work here and died. see on thailandblog, 10 feb. 2019: https://www.thailandblog.nl/achtergrond/de-onbekende-railway-of-death/

Dear Tina,

The book I've been working on for a few years and which I'm now finalizing focuses entirely on the Romusha, the 'forgotten' Asian victims who fell during the construction of the two Japanese railways between Thailand and Burma. From the material I managed to get my hands on, it appears that many more Asians have voluntarily or forced to participate in these projects than is currently thought. The death toll of 90.000 Asian victims, which had been predicted for years, must also be urgently adjusted to a minimum of 125.000… I have also - not without some effort - found material that sheds a completely different light on the Thai involvement. In my book I will discuss, among other things, the unenviable fate of a not inconsiderable group of ethnic Chinese in Thailand who were 'gently coerced' to work on these railways, but also, for example, about the fact that Thailand has been scrupulously concealed that during World War II the Thai government 'lent' the not inconsiderable sum of 491 million baht to Japan to finance the construction of the railways….

It's great that you're writing this book. Let us know when it comes out and how it can be ordered.

A romoesja (Japanese: 労務者, rōmusha: “worker”) was a laborer, mostly from Java, who had to work for the Japanese occupier under conditions bordering on slavery during World War II. According to US Library of Congress estimates, between 4 and 10 million romushas have been employed by the Japanese.

Great job Jan, indeed we should not just dwell on our 'own' victims and all the horrors that people (civilian and military) have experienced.

Been there in 1977. Then wondered how people can hate each other so much that they kill and slaughter each other. Because that's what war is. legalized murder.

I was there last week and had the comment then, the nameplate at the Dutch graves were in worse shape than the English. I have the impression that the English take more care of their military cemeteries abroad

Behind the cemetery is a beautiful Catholic church with the name Beata Mundi Regina from 1955. This church as a war memorial was an initiative of Joseph Welsing, who was the Dutch ambassador to Burma. Noteworthy is the photo of the King of Thailand next to the altar.

If you are in the area, a visit to the museum located near the cemetery is also worth a visit.

The Hellfire Pass Memorial, the memorial center founded by Australia and Thailand, is also impressive.

I've been there and it is indeed impressive. When you look at the graves, so many young people who died there. May we never forget !

After you have visited the cemetery and the museum, you must also make the train journey. Only then will you understand the whole story even better. So many dead, you see the work they did, you feel their pain and sorrow in your heart when you drive on the track.

And let's also honor the Thais who helped the forced laborers on the Thai-Burma Railway. Why is that so rarely done?

https://www.thailandblog.nl/achtergrond/boon-pong-de-thaise-held-die-hulp-verleende-aan-de-krijgsgevangenen-bij-de-dodenspoorlijn/

Visited Kanchanaburi for a few days during our winter stay in 2014 and visited the Memorial very impressive and what stood out is that it is well maintained and encountered many Dutch names

very respectful..