'The sun is scorching hot, the rain lashes in gusts,

and both bite deep into our bones',

we still bear our burdens like ghosts,

but have been dead and petrified for years. '

(An excerpt from the poem 'Pagoda road' that the Dutch forced laborer Arie Lodewijk Grendel wrote in Tavoy on 29.05.1942)

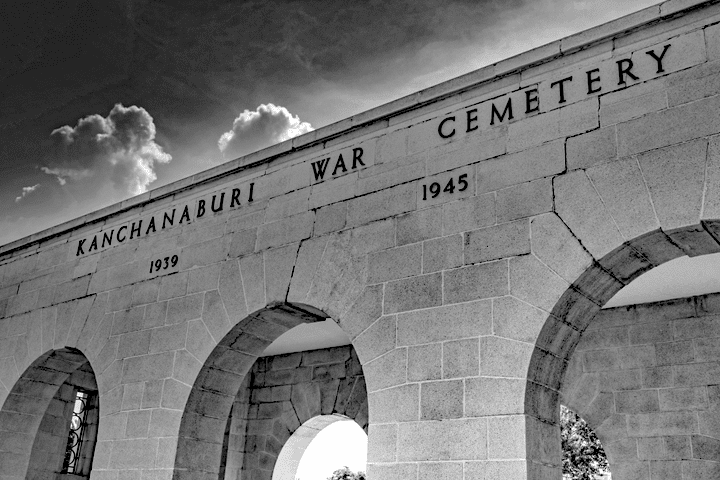

On 15 August, the victims of the Second World War in Asia in general and the Dutch victims of the construction of the Burma Railway in particular will be commemorated at the military cemeteries in Kanchanaburi and Chunkai. The tragic history of the Burma Railway has intrigued me for years.

Not only because a great-uncle of mine almost miraculously survived the construction of this railway, but also because, a long time ago, I started writing an English book that describes the too often forgotten misadventures of wanted to highlight the hundreds of thousands of Asian workers on this ambitious Japanese war project. This book may be finalized before the end of this year, and in the meantime, in my humble opinion, and after years of researching American, British, Australian, Dutch, Japanese, Indonesian, Burmese, Malaysian and Thai archives, I can as someone who knows a little more than average about this drama.

The plan of the Japanese army command was ambitious. A fixed rail connection was needed between Ban Pong, Thailand, about 72 km west of Bangkok, and Thanbyuzayat in Burma. The planned route had a total length of 415 km. In the beginning, Tokyo was not at all convinced of the usefulness of the construction of this railway, but suddenly regarded it as an absolute military necessity when the war turned in favor of the Allies. Not only to maintain the front in Burma, but also to be able to push through from northern Burma to the British crown colony of India. Supplying the huge Japanese base at Thanbyuzayat by road was a very difficult, time-consuming and consequently expensive operation. Supplying supplies by sea, via Singapore and through the Straits of Malacca, with the lurking Allied submarines and pilots, was a high-risk operation, all the more so after the defeats in naval battles of the Coral Sea (4-8 May 1942) and Midway (3- June 6, 1942), the Japanese Imperial Navy had lost its naval superiority and was slowly but surely forced onto the defensive. Hence the choice for access by rail.

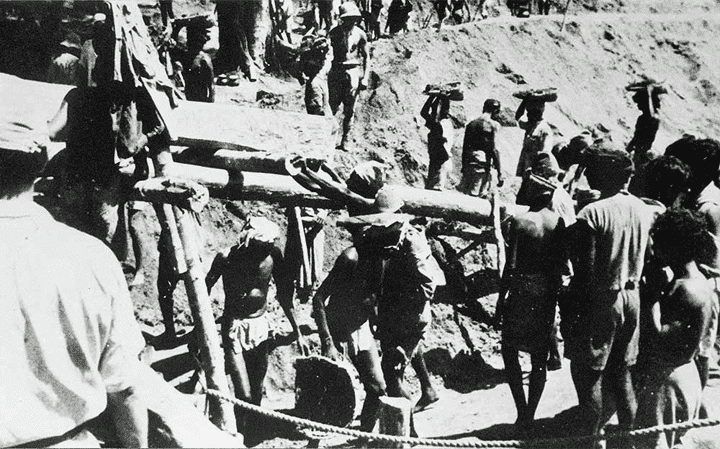

working under Japanese supervision

In March 1942, the commander of the Japanese Southern Army Command to the Imperial Headquarters for permission to build the Thai-Burma railway. However, this proposal was rejected as unrealistic at that time. Since the end of the nineteenth century, various countries and railway companies had made attempts to realize this line, but they had repeatedly had to shelve their plans. The unexpected difficulties of working in the unforgiving jungle, the steep mountains and the erratic climate with abundant rains and floods caused them to drop out one by one. Despite this rejection, the staff of the Southern Army Command on its own initiative at the beginning of May to carry out the necessary preliminary research with a view to the construction of this rail link. Apparently the preparatory work was convincing enough this time, as the order to start construction was issued on July 1, 1942 from the Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo. Normally, the construction of the railway should have started immediately in that same July month, but in fact the job did not start until November 1942. One of the many reasons for the delays experienced on the Thai side of the project was the stiff resistance provided by local landowners who threatened to lose land for construction.

Although the Japanese engineers who advised the Imperial Headquarters believed that a construction period of three or possibly even four years should be taken into account, the military situation was really not in favor of waiting that long. Consequently, the order was given to complete the job in 18 months. Final responsibility for the project lay with the Southern Expeditionary Army Group, commanded by Field Marshal Count Terauchi. The Japanese-occupied territories had already begun recruiting voluntary workers from all over Southeast Asia, the so-called romushas, as workers. But Terauchi's advisers believed this would not be enough. They proposed asking Tokyo for permission to also deploy Allied prisoners of war. However, the Geneva Convention expressly forbade the use of prisoners of war in activities that could be directly linked to the war effort. However, the welfare of the prisoners of war was as unimportant to the Japanese as the hundreds of thousands Romushas.

The Japanese Prime Minister Tojo immediately agreed to the use of prisoners of war and the first two large groups – consisting mainly of British – were sent from Singapore to Thailand in early August 1942. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the first Dutch contingent left the improvised internment camp Tanjong Priok on Java in the first week of October 1942. This group was about 100 men strong and part of a shipment of 1.800 Allied prisoners of war. The lion's share were Australians, but there were also 200 Americans in this group. They would soon become acquainted with what later became imaginative in the diaries of the survivors as the Hellship Journeys would be described. In the sweltering holds of an overcrowded freighter, with an ill-prepared pair of guards and without adequate supplies of food and drinking water, it took nearly a week for them to reach Singapore's Keppel Harbor, exhausted and weakened. They could catch their breath in the camp of Changi for a few days, but then they went back to the overheated hold of a packed boat to Rangoon in Burma. And still the end of their Odyssey was not in sight because almost immediately after their arrival in Rangoon, a number of smaller boats headed for Moulmein from where, after spending the night in the local prison, they straight line were sent to labor camps. This first, small group of Dutchmen was closely followed by larger contingents, many of whom ended up in Thailand. Even before the end of November 1942, less than two months after the first Dutch had left Java, 4.600 Dutch prisoners of war were already working on the railway. In all, between 60.000 and 80.000 British, Australian, New Zealand, Dutch and American prisoners of war would become involved in one way or another in the construction of the railway, which soon acquired a sinister reputation as Railway of Death got.

Not only the long, almost endless days - and later also nights - of heavy and physically demanding work, often accompanied by work accidents, but also the never-ending abuses and punishments would take their toll. The very irregular supplies and the resulting rationing problems were another fundamental problem faced by the POWs. The small daily rations of inferior quality and often worm-infested broken rice, which could be supplemented very occasionally with dried fish or meat, were absolutely not enough. In addition, the men were confronted daily with a manifest lack of fresh, drinkable water. This soon led to the POWs becoming malnourished and dehydrated, which naturally made them more susceptible to all kinds of often life-threatening illnesses.

In particular, the cholera epidemic during the rainy season of 1943 wreaked havoc in the camps. The outbreak of these diseases was directly related to the arrival of the first romushas. The first large contingents to operate in Thailand were not dispatched until February-March 1943. Many of them were already sick when they arrived in the Thai jungle at the beginning of the rainy season.

food distribution in a labor camp

Most surviving Allied POWs agreed after the war that the conditions in which the romushas had to survive were a lot worse than theirs. Unlike the prisoners of war, the Asian workers lacked the comfort and discipline of a military structure – a prerequisite for maintaining morale in difficult circumstances – and, worse still, they had no doctors or medical staff of their own and certainly no interpreters. They had been recruited from the poorest, largely illiterate section of their respective populations, and that would pay off immediately. While the Western POWs took hygiene-promoting measures as much as possible, from bathing – if possible – to digging latrines as far away as possible from the camps, the romushas no idea about the misery that rats or flies and contaminated water could cause. Many of them simply relieved themselves where it suited them, often in the middle of their camps or near the kitchens. The consequences were disastrous.

What no one realized, not even the Japanese, was that along with the rain came cholera. A new deadly test, which would have a devastating effect on the already weakened and sick workers. The camps were already full of victims of dysentery, malaria and beriberi anyway. Cholera is a bacterial infectious disease that is transmitted through contact with contaminated water. Highly contagious, the disease usually begins with severe abdominal cramps, followed closely by high fever, vomiting and diarrhoea, often resulting in death. In early May 1943, cholera broke out along the railway line in Burma. From an alarming report by the Ninth Railway Regiment it turned out that less than three weeks later cholera was already diagnosed in Thailand, in the camp of Takanun. At the beginning of June, the first deaths occurred in the Malaysian camp at milestone 125. The plague spread rapidly and caused raw panic among the POWs, but also and especially among the Japanese. The romushas were so overcome by the fear of cholera that both healthy and infected workers tried to flee en masse from the camps. This was often facilitated by the fact that the Japanese military, fearful of possible infections, had withdrawn from the hotbeds of contagion and contented themselves with erecting protective circles around the romusha-struggling. This panic also spread like straw among the newcomers, many of whom also promptly fled on their way to the camps. To make matters worse, the heavy rains made the roads in the jungle impassable and the already scarce food supply was seriously compromised by the supply problems.

Military Fields of Honor in Kanchanaburi

It is a remarkable finding for anyone who studies the dramatic story of the Burma railway that the Dutch contingent fared relatively best in absolute figures. That had a lot, if not everything, to do with the prisoners of war of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army (KNIL). A large part of them – unlike most British or Americans, for example – had knowledge of the native plants. They tracked down the edible specimens, cooked them, and ate them as a welcome addition to the meager meals. Moreover, they knew a lot of medicinal herbs and plants from the jungle, an alternative knowledge that was also shared by a number of the KNIL doctors and nurses who were also interned. Moreover, the well-trained KNIL soldiers, often of mixed Indisch ethnic origin, were much better able to cope with the primitive existence in the jungle than the Europeans.

Those who survived the cholera epidemic would have to work at a hellish pace for months to come. After all, the appalling death toll from the epidemic had caused a noticeable delay in railway construction and it had to be made up as soon as possible. This phase in the construction became infamous as the infame 'speedo'period in which hysterical 'speedo! speedo! screaming Japanese and Korean guards drove the POWs beyond their physical limits with their rifle butts. Working days with more than a hundred deaths were no exception…

On October 7, 1943, the last rivet was driven into the track and the route that had cost so much blood, sweat and tears was completed. After the completion of the line, a substantial part of the Dutch contingent was used for maintenance work on the railway line and the felling and sawing of trees that served as fuel for the locomotives. The Dutch also had to build camouflaged train shelters scattered along the railway lines, which were used during the increasing number of Allied long-range bombing missions against Japanese railway infrastructure in Thailand and Burma. These bombings would also cost the lives of several dozen Dutch prisoners of war. Not only during air raids on the labor camps, but also because they were forced by the Japanese to clear away duds, unexploded aerial bombs…

Military Fields of Honor in Kanchanaburi

According to data from the National Archives in Washington (Record Group 407, Box 121, Volume III – Thailand), which I was able to consult some fifteen years ago, at least 1.231 officers and 13.871 other ranks of the Dutch land forces, navy, air force and KNIL were deployed in the construction of the Railway of Death. However, it is certain that this list contains a number of gaps and is therefore not complete, which means that between 15.000 and 17.000 Dutch people were probably deployed in this hellish job. In the National Archives in The Hague I even came to a total of 17.392 deployed Dutch people. Nearly 3.000 of them would not survive. 2.210 Dutch victims were given a final resting place at two military cemeteries in Thailand near Kanchanaburi: Chungkai War Cemetery en Kanchanaburi War Cemetery. After the war, 621 Dutch victims were buried on the Burmese side of the railway Thanbyuzayat War Cemetery. The youngest Dutch soldier to my knowledge succumbed to the Railway of Death was 17-year-old Theodorus Moria. He was born on August 10, 1927 in Bandoeng and died on March 12, 1945 in the Chungkai camp hospital. This Marine 3e class was buried in grave III A 2 on it by the British Commonwealth War Graves Commission managed Chungkai War Cemetery.

Thousands of survivors bore the physical and psychological scars of their efforts. When they were repatriated to the liberated Netherlands, they ended up in a country that they barely recognized and that did not recognize them…. Enough had already been said about the war: now everyone to work for the reconstruction of the country was the national credo. Or maybe they had forgotten that the Dutch themselves had a war behind their teeth…?! Many Dutch people still mourned their own dead and missing close to home. The misery from far away, in the Japanese camps, attracted little interest. It all seemed so far away from my bed show. Shortly afterwards, the violence with which the Indonesian nationalists believed they had to achieve their independence and the subsequent equally ruthless police actions mortgaged and ultimately gave the death knell to a Dutch – Southeast Asian memory trajectory that could potentially be experienced together.

Three Pagoden monument in Bronbeek (Photo: Wikimedia)

The KNIL ceased to exist on June 26, 1950. Simply because the Dutch East Indies no longer existed. Many of the former Indian soldiers felt like outcasts treated, left the mother country and ended up in shadowy boarding houses or even colder reception camps in the Netherlands. The rest is history….

Or not quite… In the beginning of April 1986, forty-one years after the end of the Second World War, the NOS broadcast a two-part report in which three former Dutch forced laborers returned to Thailand in search of what remained of the railway. It was the first time that Dutch television paid such extensive but also so lavish attention to this war drama. In that same year, Geert Mak, who had not yet really broken through as a writer, went in search of traces of his father, who had worked as a pastor along the route of the railway. On June 24, 1989, the Burma-Siam or Three Pagoden monument was unveiled in the Military Home Bronbeek in Arnhem, so that this almost forgotten but oh so tragic page from the Second World War finally received the official attention it deserved in the Netherlands...

Thank you for this beautiful but tragic story…let's not forget the past.

And very good that you are going to pay more attention to the tens of thousands of Asian (forced) laborers where the mortality rate was higher and about which little has been written…

Dear Tina,

You are right to use brackets for (forced) workers, because the greatest drama in the tragic story of the romushas is that it is estimated that more than 60% of them voluntarily went to work for the Japanese….

In a story about our colonial past I saw a photo of the future president Sukarno who recruited workers (romushas) for the Japanese on Java, somewhere in '42-'43. In this wonderful book:

Piet Hagen, Colonial wars in Indonesia, Five centuries of resistance against foreign domination, De Arbeiderspers, 2018, ISBN 978 90 295 07172

Thank you very much for this impressive article. I am silent for a moment…..

Been there 4 years ago and visited both graveyards. Everything was taken care of down to the last detail and is kept nice and clean by the workers there. Also on the spot at the bridge you can buy a book in Dutch, THE TRACK OF DOODS. This is available in several languages. There are many photos and an extensive description. Furthermore, not to forget the museum, which still gives a good overview of what happened there through the image material.

In ”High above the trees I look back” Wim Kan Doc.1995 Wim Kan also refers to his period with this

Burma Railway.

Dear Louis,

Wim Kan's role in the labor camps and later as an activist against the arrival of the Japanese emperor Hiroito in the Netherlands were not entirely undisputed. Just read 'A rhapsodic life' by A. Zijderveld or 'Not many people live anymore: Wim Kan and the arrival of the Japanese emperor' by K. Bessems… Nevertheless, Kan remains the writer/interpreter of the poignant Burma song of which I would like to share this excerpt as a reminder:

“Not many people are alive who have experienced it

that enemy killed about a third of them

They sleep in a burlap sack, the Burma sky is their roof

The camps are deserted, empty the cells

There aren't many people alive left who can tell the story…'

Thank you for this impressive exposé. Let us know when your book (and under what name) will be released.

My father spent three years in a Japanese camp in Indonesia and did not tell much about it. I look forward to your forthcoming book….

My long-deceased father-in-law never spoke of the death railway either. He would have worked there in the infirmary, which is why I found it hard to believe that he actually worked there. After all, there was no infirmary unless it had to be a place from which the corpses were transported to a cemetery. Right?

Dear Nick,

Contrary to what you think, every Allied POW labor camp had at least one infirmary. In larger camps there were slightly better equipped hospitals. after the fall of Singapore and the Dutch capitulation on Java, entire divisions with their respective medical units became Japanese prisoners of war, and as a result there were about 1.500 to 2.000 doctors, stretcher bearers and nurses among the forced laborers on the Railway. Unfortunately, this was not the case for the Asian workers and they died like flies. At the height of the cholera epidemic, in June 1943, the Japanese, for example, sent 30 allied doctors and 200 nurses, including several dozen Dutchmen, from Changi to the stricken coolie camps…

If we ever talk about “must see” in Thailand then I think that this part of Thailand should not be skipped. Together with the 2 cemeteries (3rd is in Myanmar) and the JEATH museum.

Dear Jan, thank you for this impressive piece. And we keep an eye on that book, especially the non-Europeans could get a little more attention.

Seeing the black and white photo with the text food distribution in a labor camp.

You must have been there once in a while.

Jan Beute.

Thank you Lung Jan

For reposting your story about the death railway, especially on this day.

Our memories may never fade from this horrific part of the 2nd World War where Dutch forced laborers or KNIL soldiers had to work in harsh weather conditions and were worn out as slaves and enemies of Japan.