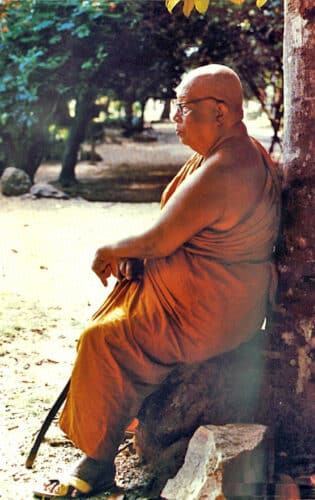

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, a great Buddhist philosopher

Buddhadasa Bikkhu is seen as the most influential Buddhist philosopher in Thailand and far beyond. His reinterpretation of Buddhism for modern times has appealed to many people in Thailand, although most of his followers are among the middle class. Below I will discuss his fresh and innovative ideas.

Deep disappointment

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (Thai: พุทธทาส ภิกขุ phóetáthâat 'Servant of the Buddha' and phíkkhòe 'monk') was born on May 27, 1906 in the village of Rumriang, Chaiya Municipality, Surat Thani, where his father, a second-generation Chinese, and his mother, a Thai, ran a shop.

After attending a temple school for a few years, he continued his studies at a state school in Chaiya. In 1922 his father died and he temporarily took over the shop, also to pay for the education of his younger brother who studied at the famous Suan Kulap school in Bangkok.

In 1926 Buddhadasa was initiated as a monk and he would never leave the monk order, the Sangha. From 1930 to 1932 he spent time at a Buddhist university in Bangkok where he met Narit Phasit (he shared Narit's criticism of the Buddhist establishment, but considered him too radical) and Pridi Phanomyong. The way Buddhism was studied, taught and practiced in Bangkok was a deep disappointment to him.

Bush monk

In May 1932, a month before the revolution that converted the absolute monarchy into a constitutional monarchy, he returned to Chaiya where he spent two years alone studying and meditating in the jungle as a forest monk. Later other monks joined him.

Buddhadasa gave the temple, set up in 1943 at another location seven kilometers southeast of Chaiya, the name Suan Mokkhaphalaram, usually called Suan Mokh (pronounced: sǒean môok): 'The Garden of Liberation'. There he would remain until his death on May 25, 1992.

All those years in the temple he spent studying, writing and preaching, aided by his younger brother Dhammadasa ("The Servant of the Dhamma, the Teaching"). His ideas were spread all over Thailand by all kinds of magazines, books and organizations. There is a book by him on the counter in every bookstore. Most people know his name and some of his ideas.

The Suan Mokh temple is visited by tens of thousands of people every year, including many foreigners, mainly for medication courses. Buddhadasa once elicited the statement from the many day trippers: 'I think all those people mainly come here for a sanitary stop…'.

Aversion to Buddhist practice and authority

Buddhadasa's years of study in Bangkok left him with a lifelong aversion to Buddhist practice and especially authority. He found the temples dirty and crowded, the monks mainly concerned with status, wealth, prestige and an easy life. The laity practiced rituals, but had little understanding of Buddhism. The authorities were more concerned with the practice of Buddhism, and in particular monasticism, than with its doctrine. Reflection on the foundations of Buddhism and intellectual activity was neglected, even among the laity.

For example, a battle raged for a long time about the correct color of the monk's habit, bright orange or somber red-brown, and the question of whether the habit should cover both or only the left shoulder. Lay people were more concerned with rituals, offerings, gaining merit and so on, and not with the core of Buddhism, an attitude encouraged by the monks.

Buddhadasa noticed that the study of Buddhism was mainly about the commentaries written many centuries after the Buddha and hardly about the sayings of the Buddha himself. He wanted to go back to the original writings.

The intertwining of Buddhism and the state was also a thorn in his side. It was especially King Rama VI who emphasized the unity of Buddhism, monarchy and the state, the Thai Trinity. One cannot do without the other.

All Thai leaders since then have endorsed this position. A person who renounces his faith or is considered a heretic is an enemy of the state, and in the thinking of the XNUMXs and XNUMXs, a "communist." So it should come as no surprise that Buddhadasa was then accused of being a 'communist' by more conservative elements in Thai society.

The first time I applied for a marriage visa in Chiang Khong, I was asked about my 'sàatsànǎa, religion'. I said 'phóet, Buddhist.' The immigration officer stopped typing, sat back and said, “You can't. You are not Thai.'

Phasǎa khon and phasǎa tham, the human language and the spiritual language

Most scriptures and sayings in all religions are written in plain language (phasǎa khon) but what matters in the end is the spiritual meaning (phasǎa tham). Buddhadasa makes a sharp distinction between them. If we want to understand the real meaning of the scriptures, we have to translate the human language into the spiritual language. Myths, miracles and legends in human language point to a deeper meaning.

The passage of Moses and the Jewish people through the Red Sea is human language, in the spiritual language it means the love of Yahweh for his people. This is how Buddhadasa also explained Buddhist myths and legends. And so 'death and rebirth', in addition to the biological event, can also mean loss of morals and vices, in addition to liberation from suffering in the here and now.

Buddhadasa wished to go back to the original scriptures, especially the suttapitaka where the sayings and deeds of the Buddha are recorded. He ignored all hundreds of subsequent comments as unimportant and often confusing.

A taboo subject: Nirvana

Nibbana (in Sanskrit better known as Nirvana) is almost a taboo subject in contemporary Buddhism. If it is spoken of at all, it is an unattainable ideal, only possible for monks, thousands of rebirths away, far from this world, a kind of heaven where you cannot be reborn in this world of suffering.

Buddhadasa points out that according to the scriptures, the Buddha attained 'nibbana' before his death. The original meaning of nibbana is "quenching," as of a set of glowing coals, or "tame," as a tame animal, cool and undefiled.

Buddhadasa believes that nibbana means the extinction of disturbing and polluting thoughts and emotions, such as greed, lust, hatred, revenge, ignorance and selfishness. It means not making the 'I' and the 'mine' the guiding principles in our lives.

Nibbana can be temporary or permanent dit life are achieved, by lay people and monks, even without knowledge of the scriptures, even without temples and monks, and also without rituals and prayers.

Buddhadasa said that he could summarize his teaching as follows: 'Do good, avoid evil and purify your mind'. That is the real reincarnation, the real rebirth.

A pure mind

'Chít wâang' or a pure mind is not really an innovative idea but one of the oldest and central truths in Buddhism wherever Buddhadasa places it. 'Chít wâang' literally means 'empty mind'. It is Buddhadasa's translation of a Buddhist concept that refers to detaching, letting go of disturbing and polluting influences in the mind.

First of all putting aside 'I' and my' (ตัวกู-ของกู toea cow-khǒng cow, striking that Buddhadasa uses the ordinary, even lower, colloquial language here), which is in accordance with the notion of an-atta 'non- yourself'. In addition, the release of intense, destructive emotions such as lust, greed and revenge. Chít wâang is a mind in balance and tranquility. Striving for this state of mind is essential.

Work is central to our lives

For Buddhadasa, work is central to our lives, it is a necessary and also liberating thing. By work, he means not only what provides for our livelihood, but all daily activities, within the family and in the community. It is therefore equally necessary for the maintenance of a just society. He sees no distinction between work and the dhamma, the teaching, they are inseparable,

Buddhadasa said: 'Work in the rice fields has more to do with dhamma, the teachings, than a religious ceremony in a temple, church or mosque.' Moreover, he felt that all kinds of work, if done in the right frame of mind, have equal value.

Karma

Karma is called กรรม 'comb' in Thai. In Sanskrit the word means 'deed, action' and a purposeful action. In the common view of Thai Buddhism, the accumulated karma from all your previous lives determines your life in the here and now.

How you are then reborn depends on the further merit, good or bad, you acquire in this life. This can best be done through rituals, visiting temples, giving money to temples, etc. Giving twenty baht to a temple improves your karma than giving two hundred baht to a poverty-stricken neighbor.

People in high regard, people with money, health and status, must have acquired a lot of good karma in a past life. Their place in society is, as it were, a birthright and therefore untouchable. The reverse also applies. This is the common Thai view.

My son's now 25 year old stepsister is disabled. Due to the hereditary disease thalassemia she is deaf and dumb. Once, twelve years ago, we traveled to a famous temple north of Chiang Rai. Her mother asked a monk, "Why is my daughter so handicapped?" To which the monk replied that it must be due to bad karma from past lives.' That stepsister with bad karma is one of the nicest and smartest people I know.

Buddhadasa's view of karma is in sharp contrast to this. He points out that the Buddha himself almost never spoke of karma, and certainly did not judge people on it. The idea of karma is a Hindu concept and existed long before the Buddha. He suspects that the Hindu idea of karma has crept into Buddhism in the later commentaries and books.

For Buddhadasa, karma is only that which produces results, good or bad, in the here-and-now. The fruits of your activities are, as it were, already present in your actions. Those fruits reveal themselves both in your own mind and in the influence on your environment.

No preference for a political system

Buddhadasa has never expressed a preference for a particular political system, except that leaders must also follow the dhamma, the teachings. Conservative leaders have rejected his ideas. Let me limit myself to a few statements:

Buddhadasa: “It is not communism that is a threat to Thailand, but exploitative and oppressive capitalism.”

Sulak Sivaraska: 'A weak point in Buddhadasa is the subject of 'dictator', because dictators never possess dhamma and we surrender too much to dictators. Even the abbots of monasteries are dictators, including Buddhadasa himself….”

Tino Kuis

Sources:

Peter A Jackson, Buddhadasa, Theravada Buddhism and Modernist Reform in Thailand, Silkworm, Books, 2003

Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, 'I' and 'Mine', Thammasapa & Bunluentham Institution, no year

www.buddhanet.net/budasa.htm

/en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhadasa

Three videos to experience Buddhadasa's life and teachings:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgw97YTOriw

www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3PmajYl0Q4

www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJvB9xKfX1U

The Four Noble Truths explained:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJvB9xKfX1U

Thanks Tina!

Good lazy piece. I now understand much more about (Thai) Buddhism. Budhadhasa's philosophy leaves little room for abuse of power. Therefore, at least among the privileged and powerful, it will not be very popular.

Sunday January 14, 2024/2567

Thanks for educational information.

I ask myself more and more why I don't put into practice the much-needed, correctly read words every day.

There are moments when I feel and understand it.

But then you soldier on again.

Deploy me more.

Thanks,