Mapping Siam – the origins of the borders and the proud nation-state

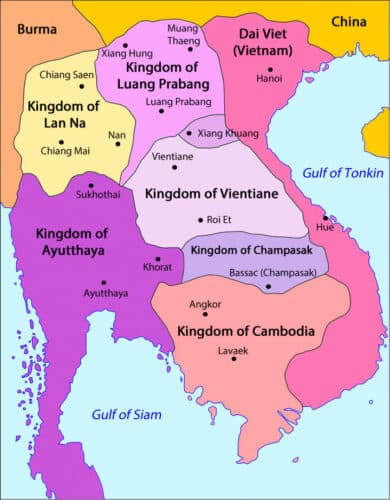

The region and its spheres of influence in 1750, before the modern nation came into being

How did today's Thailand get its shape and identity? Determining who and what exactly does or does not belong to a country is not something that just happened. Thailand, formerly Siam, did not just come about either. Less than two hundred years ago it was a region of kingdoms without real borders but with (overlapping) spheres of influence. Let's see how Thailand's modern geo-body came about.

A hierarchy of “independent” vassal states

Previously, Southeast Asia was a patchwork of chiefdoms (a system in which several communities are headed by a chief) and kingdoms. In this pre-modern society, political relations were hierarchical. A ruler had power over a number of smaller local rulers of nearby villages. However, this ruler was in turn subservient to a higher overlord. This tiered pyramid continued up to the most powerful ruler in the area. In short, a system of vassal states.

Intuitively, these (city) states were seen as separate kingdoms, also called muang (เมือง) in Thai. Although it operated within a hierarchical network, the king of the vassal state saw himself as an independent ruler of his own empire. The higher ruler hardly interfered with the rulers below him. Each state had its own jurisdiction, taxes, army and legal system. So they were more or less independent. But when it came down to it, the state had to submit to the higher ruler. He could intervene when he deemed it necessary.

These power relations were not fixed: if circumstances changed, the position of the kingdoms within this system could also change. Power relations could always change. Uncertainties in hierarchical relationships could be settled in a very concrete way: war. In times of war, the cities on the front were the first victims. They were forced to provide food and people or else were looted, destroyed and depopulated. Sometimes whole masses of people were taken as spoils of war.

tributary states

The vassal therefore had to make manpower, troops, goods, money or other goods available to the overlord on request - where necessary. In return, the overlord had to provide protection. For example, Bangkok had to protect its vassal states against Burma and Vietnam.

A vassal state had several obligations, the most important of which was the ritual of submission and the oath of allegiance. Every (few) years, a vassal state sent gifts to the higher ruler to renew ties. Money and valuables were always part of that, but most important was sending trees with leaves of silver or gold. Known in Thai as “tônmáai-ngeun tônmáai-thong” (ต้นไม้เงินต้นไม้ทอง) and in Malay as “bunga mas”. In return, the overlord sent gifts of greater value to his vassal state.

Various states under Siam were indebted to the king of Siam. Siam, in turn, was indebted to China. Paradoxically, this is interpreted by most Thai scholars as a smart strategy to make a profit and not as a sign of submission. This is because the Chinese emperor always sent more goods to Siam than Siam gave to the emperor. However, that same practice between Siam and the subject states is construed as submission, even though the rulers of those states could just as well reason that it was merely a symbolic act of friendship towards Siam and nothing more.

A French map of Siam in 1869, north of the red line the vassal states

More than one overlord

The vassal states often had more than one overlord. This was both a curse and a blessing, providing some measure of protection against oppression from the other overlord(s), but also binding obligations. It was a strategy to survive and to remain more or less independent.

Kingdoms such as Lanna, Luang Phrabang and VienTiane were always under multiple overlords at the same time. So there was talk of overlap in the power circles of Burma, Siam and Vietnam. Two overlords spoke of sǒng fàai-fáa (สองฝ่ายฟ้า) and three overlords spoke of sǎam fàai-fáa (สามฝ่ายฟ้า).

But even larger kingdoms could have more than one overlord. For example, Cambodia was once a powerful empire, but from the 14de century it had lost much influence and had become a vassal state of Ayutthaya (Siam). From the 17de century Vietnam grew in power and they too demanded submission from Cambodia. Caught between these two powerful players, Cambodia had no choice but to submit to both the Siamese and Vietnamese. Siam and Vietnam both regarded Cambodia as their vassal, while the king of Cambodia always saw himself as independent.

The emergence of the borders in the 19de century

Until mid 19de century, exact boundaries and exclusive rule were something the region was unfamiliar with. When the British in the early 19de century wanted to map the region, they also wanted to determine the border with Siam. Because of the system of spheres of influence, the reaction of the Siamese authorities was that there was no real border between Siam and Burma. There were several miles of forests and mountains that didn't really belong to anyone. When asked by the British to set an exact border, the Siamese response was that the British should do that themselves and consult the local population for further information. After all, the British were friends and so Bangkok had every confidence that the British would act justly and fairly in determining the border. The boundaries were established in writing and in 1834 the British and Siamese signed an agreement on this. There was still no talk of physically marking the borders, despite repeated requests from the English. From 1847, the British began to map and measure the landscape in detail and thus mark clear boundaries.

Determining exactly what belonged to whom irritated the Siamese, demarcating it in this way was seen more as a step towards hostility. After all, why would a good friend insist on setting a hard limit? In addition, the population was used to moving freely, for example to visit relatives on the other side of the border. In traditional Southeast Asia, a subject was primarily bound to a master rather than a state. People who lived in a certain area did not necessarily belong to the same ruler. The Siamese were quite surprised that the English carried out regular inspections of the border. Before the British takeover, the local rulers usually stayed in their towns and only when the opportunity presented themselves, they plundered Burmese villages and abducted the population back with them.

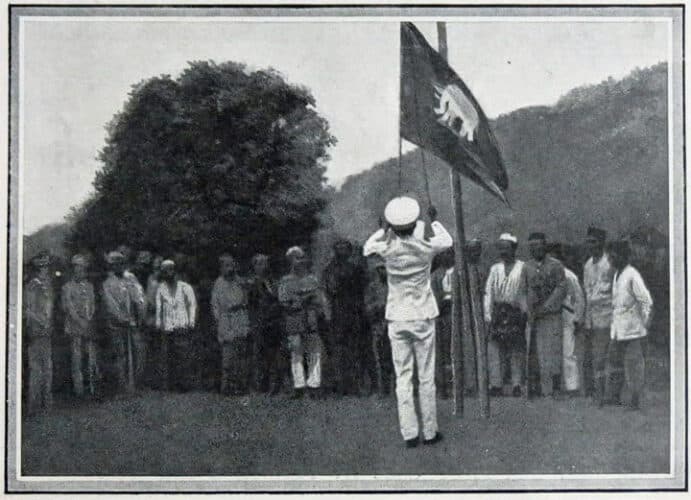

Transfer ceremony of Siamese territory in 1909

Siam permanently put on the map

Until mid 19e century, Siam was nothing like its current form. On maps, including from the Siamese themselves, Siam ran as far as just above Phichai, Phitsanulok, Sukothai, or even Kamphaengphet. In the east, Thailand was bordered by a mountain ridge, behind which lay Laos (Koraat plateau), and Cambodia. The areas of Laos, Malaysia and Cambodia fell under shared and varying rule. So Siam occupied, say, the basin of the Chao Phraya River. In the eyes of the Siamese themselves, the Lan Na, Lao and Cambodian areas were not part of Siam. It was not until 1866, when the French arrived and mapped out the areas along the Mekhong, that King Mongkut (Rama IV) realized that Siam had to do the same.

So it was from the second half of the 19de century that the Siamese elite became concerned about who owned lands that previous generations had not cared about and had even given away. The issue of sovereignty shifted influence (centers of power) from the cities to which a particular piece of land actually controlled. From then on it became important to secure every piece of land. Siam's attitude to the British was a mix of fear, respect, awe, and desire for friendship through some kind of alliance. This in contrast to the attitude towards the French, which was rather hostile. This began with the first clash between the French and Siamese in 1888. Tensions mounted and culminated in 1893, with French 'gunboat diplomacy' and the First Franco-Siamese War.

Everywhere, troops had to secure and hold an area. The start of large-scale mapping and surveying - to determine the boundaries - had started under King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). Not only because of his interest in modern geography, but also as a matter of exclusive sovereignty. It was the treaties and maps established in the period 1893 and 1907 between the Siamese, French and English that decisively changed the final shape of Siam. With modern cartography there was no place for the petty chiefdoms.

Siam is not a pathetic lamb but a smaller wolf

Siam was not a helpless victim of colonization, the Siamese rulers were very familiar with vassalship and from the mid-19de century with the European view of political geography. Siam knew that the vassal states did not really belong to Siam and that they had to be annexed. Especially in the period 1880-1900 there was a struggle between the Siamese, British and French to claim areas exclusively for themselves. Especially in the basin of the Mekong (Laos). This created more hard borders, without overlap or neutral areas and recorded on the map. Although… even today, entire stretches of the border have not been determined exactly!

It was a gradual process to bring the places and local rulers under the authority of Bangkok with (military) expeditionary troops, and to incorporate them into a modern bureaucratic system of centralization. Pace, method, etc. changed per region, but the end goal was the same: control over revenues, taxes, budget, education, legal system and other administrative matters by Bangkok through appointments. Most of the appointees were brothers of the king or close confidants. They had to assume supervision from the local ruler or take over control entirely. This new system was largely similar to the regimes in colonial states. The Thai rulers found their way of government very similar to the European and very developed (civilized). That is why we also speak of the process of 'internal colonization'.

A selective 'us' and 'them'

When in 1887 Luang Prabang fell prey to looters (the local Lai and Chinese Ho), it was the French who brought the king of Luang Prabang to safety. A year later, the Siamese secured Luang Prabang again, but King Chulalongkorn was concerned that the Laotians would choose the French over the Siamese. Thus was born the strategy of portraying the French as the foreigner, the outsider, and emphasizing that the Siamese and Lao were of the same descent. However, for the Lao, Lai, Theang, etc., the Siamese were just as much "they" as the French and not part of "we".

This selective image of “us” and “them” came into play early in World War II, when the Thai government released a map showing the losses of the glorious Siamese empire. This showed how the French in particular had consumed large parts of Siam. This had two consequences: it showed something that had never existed as such and it turned pain into something concrete, measurable and clear. This map can still be found today in many atlases and textbooks.

This fits the selective historical self-image that the Thai once lived in China and were forced by a foreign threat to move south, where they hoped to find the promised “Golden Land” (สุวรรณภูมิ, Sòewannáphoem), already largely occupied by the Khmer. And that despite adversity and foreign dominance, the Thai always had an independence and freedom in them. They fought for their own land and so the Sukhothai kingdom was born. For hundreds of years, the Thai had been under threat from foreign powers, especially the Burmese. Heroic Thai kings always helped the Thai triumph to restore their country. Every time even better than before. Despite foreign threats, Siam prospered. The Burmese, the Thai said, were the other, aggressive, expansive, and warlike. The Khmer were rather cowardly but opportunistic, attacking the Thai in times of trouble. The characteristics of the Thai were the mirror image of this: Peaceful, non-aggressive, brave and freedom-loving people. Just as the national anthem tells us now. Creating an image of “the other” is necessary to legitimize political and social control over rivals. The Thai, being Thai and Thainess (ความเป็นไทย, came pen Thai) stands for all that is good, in contrast to the other, the outsiders.

In Summary

In the last decades of the 19de century the patchwork of kingdoms came to an end, only Siam and its great neighbors remained, neatly mapped. And from the beginning of the 20th century, the inhabitants were told that we belonged to the proudest Thai people and not.

Finally, a personal note: why Siam/Thailand never became a colony? For the parties involved, a neutral and independent Siam simply had more advantages.

Resources and more:

- Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of the Nation, Thongchai Winichakul, Silkworm Books, ISBN 9789747100563

- The battle between the Siamese and the French: https://www.thailandblog.nl/achtergrond/kanonneerbootdiplomatie-de-eerste-franco-siamese-oorlog-1893-deel-1/

- About who is and is not seen as 'Thai': https://www.thailandblog.nl/achtergrond/isaaners-zijn-geen-thai-wie-mag-zich-thai-noemen-het-uitwissen-van-de-plaatselijke-identiteit/

- Nationalism and the creation of Thai identity: https://www.thailandblog.nl/achtergrond/echos-uit-het-verleden-luang-wichit-wathakan-en-het-creeren-van-de-thaise-identiteit/

To this day we can read how much area Siam had to “give up” and the incorrect suggestion that the country was once much larger by projecting the modern nation-state to where the Siamese had influence. The 'lost' Siamese territories on a map, see:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Siamese_territorial_concessions_(1867-1909)_with_flags.gif

Rob V, thanks for another interesting contribution.

Rob V, thank you for this article. But one thing I don't quite understand. That's this sentence in your story.

For example, Bangkok had to protect its vassal states against Burma and Vietnam. Shouldn't that be Ayuttaya, the then capital?

Dear Ruud, you're welcome, it's nice if more than 3-4 readers appreciate the pieces (and hopefully learn something from them). Ayyuthaya had to take neighboring kingdoms into account as well, but here in this piece I focus on the period 1800-1900, with the last decades in particular. Ayutthaya fell in 1767, the elite moved / fled to Bangkok (Baan Kok, named after a kind of olive plant), and a few years later the king moved across the river and built the palace that we still see today. know. So in the 19th century we talk about Siam/Bangkok.

Thank you Rob. Of course Bangkok I had focused too much on the accompanying map.

It's just what you call yes: Bangkok protected its vassal states against Burma and Vietnam. Bankok defended himself through his vassal states. The local elite may have preferred Bangkok, but the local population did not always see its importance there.

You can also speak of buffer states.

Thank you Rob V for this nice article. I was aware of the existence of the early Thai kingdoms as well as the later struggles with the English and French in the region. But I hadn't read about these backgrounds before. Very interesting!

Informative piece, thank you.

And old maps are always welcome!

Nice contribution, Rob, and read with great interest. In the past lies the present' appears to apply once again!