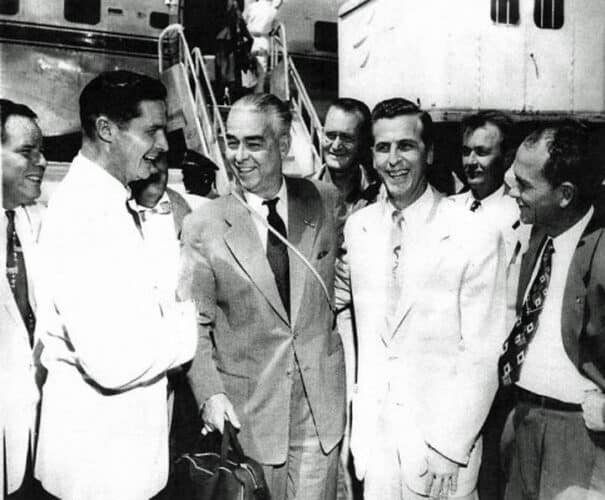

Doctor Hekking among American war veterans (Photo: The Indo Project)

In many places, including Thailand, this period commemorates the 76th anniversary of the end of World War II with the capitulation of the Japanese armed forces. Today I would like to take a moment to reflect on the Dutch doctor Henri Hekking, who was honored as a hero in the United States, but hardly gained fame in the Netherlands, and this completely unjustly.

Henri H. Hekking was born on February 13, 1903 in Surabaya on the Indonesian island of Java, then one of the jewels of the Dutch colonial empire. His interest in medicinal herbs and plants was aroused at a very young age. This was thanks to his grandmother, the Zeeland grandma Vogel, who lived in Lawang, a mountain town on the edge of the jungle above Surabaya, and who had a solid reputation as a herbalist. Henri was sent to her when he had malaria and after his recovery he went out with his grandmother when she went looking for medicinal plants in the jungle or bought them at the markets in the surrounding area. Twice a week she passed by the kampongs to help the native sick with her medicinal preparations. Perhaps the knowledge he gained first-hand encouraged him to study medicine later on.

In 1922 he enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine in Leiden with a grant he had received from the Ministry of Defence. After graduating in 1929, the brand new doctor was allowed to choose a career in Suriname or the Dutch East Indies. It became, without hesitation, his homeland. After all, as compensation for the fact that his studies were paid for by the army, he was contractually obliged to serve ten years as an army doctor in the ranks of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). Initially he was stationed in Batavia. But due to the rotation system for military doctors used by the KNIL, he changed his station every two years and then ended up in Malang and later in the garrisons of Celebes and Soerabaja.

The young doctor not only trained himself in combating tropical diseases, but also deepened his knowledge of the beneficial plants and herbs. The latter was somewhat mockingly dismissed as quackery by some of his more conservative colleagues, but this criticism left Hekking cold. Life 'in the Eastapparently he liked it and when his contract was up he resigned. Instead of going on a well-deserved long leave to the Netherlands, Hekking went to study surgery in Italy. In September 1939 his studies were abruptly interrupted by the suddenly very real threat of war and the mobilization of the Dutch army. In the beginning of 1940 we find captain-medical second class Henri Hekking with his wife and two children in his new station on the western, Dutch part of the island of Timor.

On February 19, 1942, the Japanese Imperial Forces attacked Timor in full force. The allied troops, a mix of British, Australians, New Zealanders, Indians, Americans and of course the Dutch from the KNIL, could hardly hold their ground and capitulated on 23 February. Doctor Hekking was taken prisoner of war and transferred to the barracks of the 10e battalion cyclists in Batavia. His family was interned in a civilian camp on Java.

When the Japanese plans for a railway between Thailand and Burma became more and more concrete, Hekking was shipped to the immense Changi prison in Singapore, along with several thousand fellow sufferers. He reached Singapore unscathed and left in August 1942, by train, in a crammed animal wagon, to the base camp at Nong Pladuk where he was given kitchen chores.

Nearly a thousand American prisoners of war were used by the Japanese during World War II for the construction and maintenance of the Thai-Burma railway. The lion's share of this contingent were marines, crew members of the USS Houston, an American heavy cruiser, sunk on 28 February 1942 during the Battle of the Java Sea. These men, mostly Texans, had been sent from the assembly camp in Changi (Signapore) to Thailand where they had to work on the railway from October 1942. In the huge Japanese base camp near Kanchanaburi, they had become acquainted with the now transferred doctor Hekking, who, despite the manifest lack of conventional medicines, had helped a number of their patients very quickly and above all efficiently with medicinal plants. A few weeks later the Americans were marched towards the wharves at Hintok.

There were a few British doctors in the camps near Hintok, but they had a knack for preventively amputating injured or infected body parts. The Americans had little faith in them modus operandi and managed to bribe one of the Japanese officers of the Railway Corps with two expensive wristwatches. They got him to transfer Doctor Hekking to their camp. Hekking used his intimate knowledge of the plants that grew literally a few feet from the camp to successfully combat disease and strengthen the weakened men. The Americans soon realized that they had done a golden thing by bringing in Hekking.

The Dutch camp doctor, who quickly nicknamed 'Jungle Doctor' became gifted, excelled in improvisation and innovation. With patiently sharpened spoons – without anesthesia – the festering tropical ulcers were scraped out, leeches diligently collected in jars to be used in due time and shirts torn into strips were boiled over and over again to serve as bandages. Very occasionally, Hekking even managed to steal medicines from the Japanese pantries, at the risk of being caught if caught…. It should not be forgotten in this context that the doctors in the labor camps, like all other prisoners of war, were not exempted from chores to perform their job. In other words, like their peers, they had to participate every day in the construction of the Thai-Burmese Railway of Death. Practicing medicine was only possible in their 'spare time' after working hours. A job that Doc Hekking managed to successfully complete thanks to his great expertise and knowledge. While in other camps the prisoners died like flies, of the approximately 700 men under his responsibility, 13 succumbed. Not one of these American prisoners had to undergo an amputation while Hekking was their camp doctor….

Hekking was a hero to the American war veterans. From 1956, when the USS Houston CA-30 Survivors Association was founded, he was their guest of honor at the Dallas reunions many times. In November 1983, he was officially honored in the United States Congress, the House of Commons. In the official US Congressional Record stated Otto Schwarz, one of his former patients:…He is not a mere physician. his practice of medicine under the worst conditions was not restricted to the attempt to heal the physical body; it also brought out his ability as a psychologist, to somehow treat the mind, spirit and soul of those prisoners of war who had little or no reason to be confident about the future…”. In 1989 the Dutch received Jungle Doctor a personal letter of thanks from US President Ronald Reagan. Reserve Major Hekking was even given the honorary rank of Vice Admiral of the Texan Fleet, part of the United States Merchant Marines. His important role in the labor camps is highlighted in at least five American books. Gavan Daws described in Prisoners of the Japanese (1994) Doc Hekking as “the master treater of mind and body”.

However, Doctor Hekking was not a sant in his own country. In the post-war Netherlands, steeped in sobriety, you could – the national credo “just act normal “mindful – but better not stick your head above the mowing field. Apart from a few newspaper articles and one mention in the standard work Workers on the Burma Railway van Leffelaar and Van Witsen from 1985, there is no trace of this more than deserving doctor in Dutch war historiography. And he was by no means the only war doctor to receive this stepmotherly treatment. Ten doctors who had served in the KNIL were nominated for a ribbon in the Order of Orange-Nassau for their exceptional services during the war. In the end, only one of them, namely Henri Hekking, would actually be awarded it, according to the testimony of his friend and colleague doctor A. Borstlap, who had been in a camp on Celebes, this happened “because they had no choice because the Americans had already given him a medal….”

In an interview conducted on November 11, 1995 in Trouw appeared, his daughter said that her father hardly spoke about his camp years at home “Only if there was reason to. Then you always got to hear very colored stories, humorous, but too positive, never the real misery. He told the highs, he skipped the lows. He didn't want to talk about that…” Doc Hekking died in The Hague on January 28, 1994, barely two weeks before his 91e birthday. He had survived the hell of the Thai-Burma Railway for just under half a century…

Memorably for such a man, ribbons are superfluous, but "only" the tradition through memories and the always spoken word counts." the real” tradition.

With Praise and Honor…Selamat Jalan dr Hekking.

That is true “immortality”…

Thanks again Lung Jan for this story and personally this raises mixed feelings and questions.

Did the whole event of the 2nd world war and the war to let go of Indonesia ensure that people were not allowed to come above ground level to mask their own mistakes?

How could it have happened that the use of medicinal plants in the Netherlands could be demonized to such an extent and that this was even regulated in an EU context as a potential threat to public health?

Who determines which history is important to include in the lesson booklets?

Hi Johnny,

Interesting question to which I cannot easily formulate an answer... What I do know from my thorough study of the Thai-Burma Railway(s) is that almost all Western historians agree that the Dutch KNIL prisoners of war, in the event of illness or injury, had a much higher percentage chance of recovery than their peers from the British Commonwealth. The captured KNIL doctors were - unlike the other Allied army doctors - without exception trained in tropical medicine and many of the KNIL soldiers were born and raised in 'De Oost' and knew, for example, the effects of things such as quinine bark. Unfortunately, the higher chances of survival did not alter the fact that many KNIL forced laborers died due to starvation, exhaustion and other hardships...

My father survived camp life as a KNIL prisoner of war by eating tjabe rawit and lombok merah that he found while working on the railway

Many thanks for this impressive story!

For me, Dr. Heking is also a hero, as are other doctors to whom many prisoners owe their lives

to have

Very impressive story.

Aren't those Americans much better at honoring the real heroes? Can we in the Netherlands learn something from our stupid ribbon rain every year. If you have worked in the town hall for 40 years, you will receive a ribbon here. Laughable!!!!!

Wow….. what a hero, this doctor!!! And what an interesting piece of history, a beautiful story. RIP dr. fence

Very well written and indeed: Selamat Jalan Dr Hekking.

A real hero.

Thank you Lung Jan for posting this reminder.

Nice story again, Lung Jan.

I am writing a story about the many Thais who helped the forced laborers and prisoners of war, especially the hero Boonpong Sirivejaphan. He also received a Dutch royal decoration.

It is a pity that the Thai heroes are mentioned so little.

Lung Jan thanks again, Tino, I'm curious.

That it's Dr. Fencing story unknown to 99.9% of people has to do with not wanting to honor people because this is seen as nationalistic and I have no idea what's wrong with nationalism in a healthy form.

The annual ribbons are a nice expression of appreciation, but it sometimes remains cosy, and if you don't have the right contacts, you will never get it.

I can only appreciate that Lung Jan brings this to the forefront.

In the Netherlands for several years now, veterans have been much better appreciated and cared for.

By that I mean those who have worked under war conditions.

I should know, wherever I go for commemorations or veterans' days, I get free transport for 2 people.

do I walk or ride during the veterans day in The Hague.

When you see how many people are there, applauding.

Good food and drink, and entertainment is also available.

Also Veterans Day Marine, Den Helder, Air Force Leeuwarden,

And that there is a care home for the veterans, which falls under the defense.

https://www.uitzendinggemist.net/aflevering/531370/Anita_Wordt_Opgenomen.html.

see the satisfied veterans. recorded, just before the pandemic, during the pandemic and after.

Hans van Mourik

Wonderful memory of a true hero. People do not want to hear this in the bourgeois sprout culture.

Although I am a real cheesehead, my late wife's family is from India and I have always felt that I was born in the wrong country.

Many of my friends and acquaintances came from the camps after the war but hardly ever spoke about it because then the reactions that Kees van Kooten, a classmate, later described so beautifully from the Dutch resistance heroes "do ist die bahnhof" as their heroic contribution.

In my immediate vicinity I had survivors of the Burma railway as well as the coal mines in Japan or kampetai torture. These people have been through more than 99 percent. of the ribbon carriers. I revere these compatriots in my own way. Thanks for the article.

Dick41

If he were an American, Hollywood would have already made a movie. You could write a great book about this.

That the people, then, were not so honored.

Was a different time.

Can only talk about my time.

At the end of 1962 the agreement was signed with Indonesia regarding Nw.Guinea.

Where I have been for over 2 years, and have experienced the necessary actions.

I received my medal, from my master baker, right in my hand

Arrived in Den Helder, on leave and save yourself.

In 1990 I went to Saudi Arabia with the first wave of war for 4 months.

In 1992 also 4 months in Villafranca (Italy) because of Bosnia.

For the last 2, we first went to Crete for 2 weeks, where a few Physicists and Doctors are ready to take care of you, but we drank a lot.

Upon arrival in the Netherlands, a whole ceremony with the whole family, with the medal presentation.

(1990 and 1992 I was at the KLU as a VVUT F16 specialist and never experienced anything).

Hans van Mourik

Then it was different times.

With the appreciation of these people (heroes)

I myself see the difference between 1962 when I came back from. New Guinea.

A big difference with the return of 1990 and 1992.

We owe this to the experiences of the Americans returning from the Vietnam War.

Because there are many veterans who suffer from PTSD much later.

Now it becomes much more public, people talk about it more easily.

See my last comment from broadcast missed.

They are all people over 80 who can talk now.

Hans van Mourik

We Belgians have Father Damiaan, but that doctor should certainly be next to it for his contribution in very difficult circumstances! It is a shame that this man is not honored in the Netherlands. If it were a good football player, it would be very different grrr!