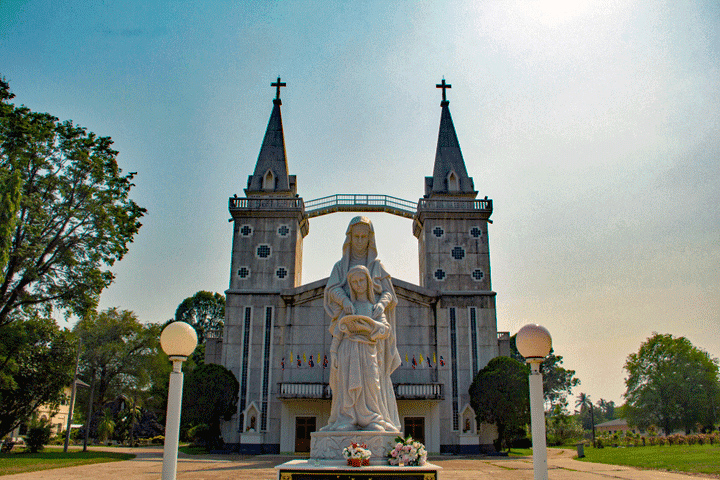

The Church of Saint Anna Nong Saeng in Nakhon Phanom

In the years 1940 to 1944, the Catholic community in Thailand was persecuted for being seen as a 'fifth column' in the conflict with French Indochina.

The Lost Lands of Siam/Thailand

In 1893, a French warship sailed up the Chao Phraya River and aimed its guns at the Siamese Royal Palace. Negotiations took place there over the demand of the French to gain control of areas that Siam considered her own, a province west of the Mekong about the height of Luang Prabang, and a number of provinces in the north of Cambodia. Partly on the advice of foreign advisers, King Chulalongkorn tacked. This event left a lasting trauma in the Thai experience of history, but at the same time King Chulalongkorn was praised for keeping the peace and preventing further colonization of Siam.

The 1940-1941 war to recapture lost territories

The trauma of the 'lost' territories festered in the Thai consciousness and emerged to a greater extent during the premiership of Nationalist Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhraam (Phibun Songkhraam, 1938-1944). He admired fascist Italy and Japan.

In 1940 France suffered a sensitive defeat against Germany. The Japanese took advantage of this, demanded and obtained a military base in French Indochina. Nationalist and anti-French demonstrations took place in Bangkok, while the government also increased its rhetoric.

From October 1940, Thailand carried out air raids on Laos and Cambodia. Vientiane, Phnom Penh, Sisophon and Battambang were bombed. The French also attacked Thai targets in Nakhorn Phanom and Khorat. On January 5, 1941, the Thai army began an attack on Laos where the French were quickly driven out, and on Cambodia where they put up more resistance. Two weeks later, the Thai navy suffered an ignominious defeat in a naval engagement near Koh Chang.

Partly through the mediation of the Japanese, an armistice was signed on a Japanese warship on January 31, 1941, while in May of that year Vichy France ceded the disputed areas to Thailand in a treaty, but only part of what Thailand had conquered. This was the cause of great revelry in Thailand, in which the Japanese and Germans participated, and was the reason for the building of the 'Victory Monument'.

In 1947, Thailand had to return these conquered territories to France under international pressure and in order to become part of the international community.

Bishop Joseph Prathan Sridarunsil at inauguration ceremony on November 10, 2018 in Hua Hin

The persecution of the Catholic community

The governor of Nakhorn Phanom wrote a letter to the Ministry of the Interior on July 31, 1942:

'The province works closely with the population tothe Catholics) to teach and train them how to repent as patriotic citizens and continue as good, alms-giving Buddhists. We always follow the policy of removing Catholicism from Thailand. Those who return to Buddhism no longer follow Catholic customs. They want to live strictly according to the applicable laws.'

The influence of the Christian community in Siam/Thailand was almost always accompanied by a certain mistrust on the part of the authorities. Christians often refused to perform chores, pay taxes, and broke away from debt bondage supported by foreign consulates (particularly England and France) who had extraterritorial rights. Sometimes this led to violence, such as the execution of two converts in 1869 by order of the king of Lanna (Chiang Mai). In 1885, a group of Catholics stormed Wat Kaeng Mueang in Nakorn Phanom and destroyed Buddha statues and relics. After a violent reaction from the Siamese authorities, consultations between the parties resulted in a solution.

At the start of the skirmishes in November 1940 to recapture the 'lost territories' from the French colonial power, the government declared martial law and all French people had to leave the country. Furthermore, the Phibun government formulated a new policy. Catholicism was called a foreign ideology that threatened to destroy traditional Thai values and was an ally of French imperialism. It had to be eliminated. Governors of the provinces bordering French Laos and Cambodia had to close churches and schools and ban services. This happened on a large scale in Sakon Nakhorn, Nong Khai and Nakhon Phanom.

The Ministry of the Interior expelled all priests from the country. Confusion arose because there were also many Italian priests while Italy was an ally of Thailand.

In a number of places, the population stormed churches and destroyed the interior. In Sakon Nakhorn, monks also participated. More serious was the killing of seven Catholics by police in Nakhorn Phanom because they refused to stop preaching and urged others not to give up their faith. They were later accused of espionage. The pope later proclaimed these seven martyrs.

A shadowy movement called "Thai Blood" spread propaganda against the Catholics. She called Buddhism essential to Thai identity. Catholics could never be real Thais, were often foreigners, wanted to enslave the Thais and formed a 'fifth column'.

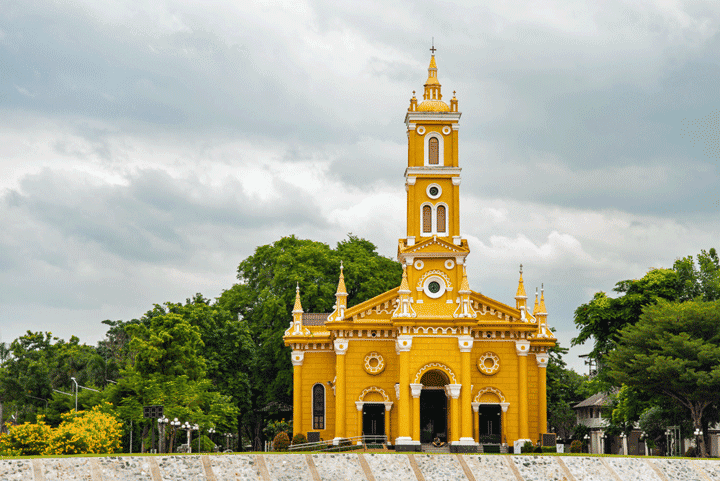

Saint Joseph Catholic Church on the banks of the Chao Phraya River near Ayutthaya

In many places in Isan, but also in the province of Chachoengsao, the authorities organized meetings where Catholics were summoned to give up their Catholic faith and return to the one and only Thai religion, on pain of losing their jobs and other threats. A district head said: 'Whoever wants to become a Buddhist again can sit on the chair, whoever wants to remain a Catholic must sit on the floor'. All but a few sat down on the floor.

Even after the armistice at the end of January 1941, persecution and intimidation continued. It only ended in 1944 when it became clear that Japan was going to lose the war and Prime Minister Phibun resigned (August 1, 1944) to make the Allies more favorable.

After the war

England considered Thailand a hostile nation and demanded money and goods (rice) in compensation. America was more lenient in its judgment, referring to the Free Thai movement that had opposed the Japanese. France insisted on returning the 'lost territories'.

Thailand was eager to join the international post-war community. The influential Pridi Phanomyong advocated good relations with America and the European powers, including France, though he rejected colonialism and entered into relations with the Vietminh liberation movement.

In October 1946 there were fierce discussions in the Thai parliament about the French demand to return the 'lost territories', which was supported by other powers. It was a choice between surrender or fight. With regret, the parliament eventually opted for restitution and peace. The bitter feelings about this can be felt to this day, such as in the turmoil around the Preah Vihear temple, which is claimed by both Thailand and Cambodia and where fighting in 2011 left dozens dead.

And it was precisely Phibun, he who had conquered the 'lost territories' in 1941, who staged a coup d'état in November 1947 and then officially returned the 'lost territories' to France.

Many Thais therefore call the 'Victory Monument' a monument of 'Humiliation and Shame'.

Main source:

Shane Strate, The Lost Territories, Thailand's History of National Humiliation, 2015 ISBN 978-0-8248-3891-1

If you cede territories, you can keep "peace" and Chulalongkorn will be praised!

Thailand has therefore never known colonization!

Something like "if you close your eyes, it doesn't exist".